podcast

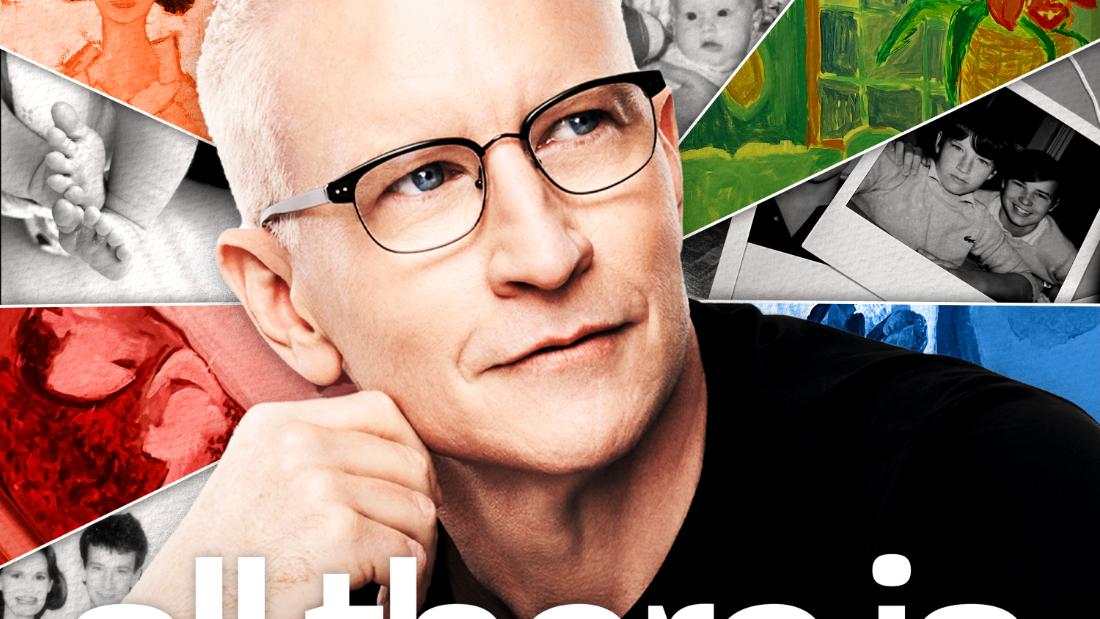

Anderson Cooper takes us on a deeply personal exploration of loss and grief. He starts recording while packing up the apartment of his late mother Gloria Vanderbilt. Going through her journals and keepsakes, as well as things left behind by his father and brother, Cooper begins a series of emotional and moving conversations about the people we lose, the things they leave behind, and how to live on – with loss, with laughter, and with love.

Anticipatory Grief All There Is with Anderson Cooper Oct 12, 2022

Filmmaker Kirsten Johnson lost her mother to Alzheimer’s in 2007, now her father has dementia, and is disappearing before her eyes. As Kirsten struggles with grief over the inevitable loss of her father, she finds ways to celebrate his life and get closer to him. She tells Anderson it’s never too late to get to know someone you love more deeply even after they are gone.

I spent much of this past weekend, as usual, in my basement, going through boxes from my mom’s apartment. Saturday night, when my kids were asleep, I decided to try and wade through as much stuff as I could. I started around 8:30 p.m. and when I next looked at my phone it was almost 1 a.m.. I try to stop on a high note too, when I found a bunch of my mom’s paintbrushes, I called it a night. They’re probably the things that remind me of her the most. They smell like turpentine and paint. It’s the smell of every studio she ever had. And I just think it’s amazing how a smell can bring you back and bring you to tears. In the same box. I found a picture of a birthday party for my brother Carter. He was maybe four years old. He and my mom are in the foreground of the photo, but in the background there’s this blurry image of one of the most important people in my life. Though I’ve never really talked much about her publicly.

Her name is May McLinden. She hated being photographed, so there aren’t a ton of pictures of her. Mae was my nanny from the time I was born till I was about 15. But she was much more than that. She was a mom to me, as important to me as my mom and my dad. And she still is. Even though she died after a ten year struggle with dementia in 2014. May was from Scotland, near Glasgow. She didn’t suffer fools gladly, but she was funny and loving and our bond was extraordinary. She lived with us and after my dad died, she was the person I could depend on more than anyone. May took care of me when I was little, but she’s also the one who taught me to take care of myself, to not sit around, to make decisions, and to make things happen. As a kid, every night before I fell asleep, I would pray that one day I would make enough money to take care of May and get her a house and take her on trips to places that she always wanted to visit. As often happens with parents nannies. My mom was hurt by the closeness of my relationship with May, and one day she fired her without any warning. I came home and May was packing her things, trying not to cry in front of me. It was awful. May was 60 years old and I was her son. She was a mom to me, and there was nothing she or I could do.

May and I remained extremely close for the next 32 years of her life. We met for meals. We talked on the phone. Eventually, she retired and moved back to Scotland. When I started to earn some money, we took trips together to Los Angeles, Edinburgh, Rome. Over the years, I saved up to surprise her with a house of her own. But by the time I could do it, May had begun to decline. When she was around 80, her hearing got a lot worse than it already had been, and phone calls became difficult. I’d ask May how she was, but she usually dismissed my questions, preferring instead to hear about what I was doing, what my friends, many of whom she knew, were up to. If I was happy, May was happy, and I wanted to make her happy more than anything else in the world. May started mentioning occasionally that she was taking care of a baby. She had nieces and nephews, and I figured as one of their grandkids, but I didn’t ask more. Then a couple of weeks went by and I couldn’t reach her on the phone. I got in touch with a local minister and asked him to check on her. He did, and he called me back and told me that May had been found wandering on the street, disoriented. She was clutching a small ceramic dog wrapped in a blanket. Turns out that was the child she’d been telling me about. The one she said she’d been caring for. The dog was a present I’d given her for her birthday when I was maybe 12 years old.

“There’s one more thing,” the minister told me, “The dog she was holding, the one she thought was a child. She thought it was you.” I flew to Scotland and found May in a hospital. Her sister and I were able to connect and eventually we got her place in a really nice nursing home, a private room where she ended up living the last ten years of her life. The staff would tell me that May talked about me all the time. Her room was filled with my pictures, little things I’d given her over the years, cards and drawings I’d made for her. One time when I visited, there was a new nurse and she asked me, “Is she your mum?” “Yes.” I said, “Yes, she is.” Watching her decline. Watching all the dreams I’d had of giving her a house or having her live with me when I had kids one day. Watching all that disappear was- it was like nothing I’d ever experienced. It was a different kind of grief. Different than my mom. Different than my dad. My brother. After a time, May stopped speaking words. When I’d visit, she still knew who I was, but she’d open her mouth. And the only sound that came out was a single note, like she was singing. Ahhhh. Ahhhh.

Eventually that stopped as well. I got to see her shortly before she died. By then, she’d retreated deep inside herself. Her eyes were shut, her hands curled tight into balls. I sat with her, holding her, and I thanked her as I had a thousand times over the years. And I told her again what I told her every night before I went to bed and every time I talked to her on the phone, I told her I loved her. May McLinden died February 6, 2014, at the age of 92. Her death didn’t make headlines. The world kept spinning. But for me, on that day, it stopped. Of all the people in my family who I’ve lost, I continue to talk with May the most. When I hold my sons, when I dress them, when I put them in their cribs and it gives them goodnight. It’s her hands holding them. It’s her eyes. I see them through and I can feel her beaming with joy. May McLinden came into my life and showed me what love is, and that is what she has become in me. This is all there is.

My guest today knows all about losing people to dementia. Her name is Kirsten Johnson. She’s a filmmaker. Kirsten’s mom, Katie Jo, died in 2007 after seven year struggle with Alzheimer’s. Now, Kirsten’s father, DIck Johnson, has dementia. I read something Kirsten said about how she believes it’s never too late to get to know someone you love more deeply, even if they’re already gone. And I found that really intriguing. Kirsten is already grieving, anticipating the loss of her father, but she wanted to figure out a way to celebrate his life and get closer to him. And she ended up making a movie with him. This is Kirsten in the film.

So just the idea that I might ever lose this man is too much to bear. He’s my dad. But now it’s upon us. The beginning of his disappearance. And we’re not accepting it. He’s a psychiatrist. I’m a camera person. I suggested we make a movie about him dying. He said yes.

The film is poignant and profound, but it’s also funny and totally unexpected. You can watch it on Netflix. It’s called Dick Johnson Is Dead. Now, I just want to point out her dad is not dead. In fact, we’ll talk with him in this interview, but I’ll explain the film title later. One of the things I heard you say is that the pandemic has opened every human up to the experience of anticipatory grief. And I hadn’t really thought a lot about anticipatory grief, but I think it’s a good term. You said we don’t know how much we’re going to lose and we’re afraid of how much we’re going to lose. And if you love a person with a degenerative disease, you have a great deal of experience with anticipatory grief.

Yeah. So, I mean, I didn’t know the term anticipatory grief before my mom got Alzheimer’s, but it’s this this crazy feeling of imagining the person dead while they’re in front of you and then all the feelings that that brings. There’s a lot of guilt in it. There’s a lot of just confusion in it because it’s almost sort of unbearable. The fact that they’re not quite themselves already and then the fact that it’s going to get worse, it’s like you’re on quicksand or something. In some ways, like I was completely blindsided by the possibility that my mom gets sick and dies. Like what? This isn’t supposed to happen. And then I was double what with my dad. Like, no way. There’s no way he’s getting dementia. There’s no way he’s dying. I’ve done it once. I’m done.

You’ve said that you’re in this strange place and mourning him, who he was. Talking about your father while he’s still alive. Can you talk about that kind of limbo space?

Yeah. Yeah, well, I mean, I would say where I really enjoyed my relationship with my father throughout my life was that he was a person who just, like, met me with respect and curiosity always. Right. So that was something I really loved and needed, you know, because my dad, we could sort of grapple with the difficult stuff of life together. So when he started to get dementia, I was like, I am losing that. And suddenly I was the one who had perspective. And he wasn’t, you know, he had lost his context. And then it was slipping around, right? Like sometimes we really could get into it and have this amazing conversation and then all of a sudden, boom, the sentence would repeat, and I would realize, like, he’d lost the thread. So that kind of limbo, it’s just disorienting. One of the classic stories I tell is him waking up in the middle of the night extremely worried that a patient is downstairs. And I can’t convince him logically that the patient is not there. So then I go downstairs with him. Then what happens? He looks around, he’s like, There’s no patient. And he’s like, Oh, you were right. And then he says, It must be incredibly difficult to watch your father lose his mind.

Wow. Oh. So he’s had the self-awareness of what was happening to him

Yes. That would go in and out. But when it was in, you know, it’s like a knife in your heart.

Your mother did not have that self-awareness.

She- she did not know she was losing her mind.

My name’s Johnson. What’s my first name? I give you a hint? I’m your daughter.

I feel such tenderness for both of us in that moment. Like, I’m just like, Come on, Mom. Like, you got to know who I am. And the look in her eyes. Like she knows she’s being asked that and that she doesn’t know the answer. And then she’s sort of like, you know, tries to search around and be like, you’re a Johnson, right? And it’s like, yeah. But I mean, I’m just in that limbo of like, there’s still got to be some part of you who knows me.

We still need things from our parents, some understanding, some peace of love, whatever it is. There never comes a time when you don’t sort of hope, I think. Unless you’ve had a terrible relationship with the parent, you don’t sort of hope that even in their decline that they can still be there for you.

Mhm. Totally. What I find fascinating is. My mom is so present with me, absolutely. You know, I was riding up here on the bicycle and I was just, like thinking of her and, you know, by some pictures of her. And you’ve said her name and I’ve heard her voice and I’m gesticulating and I can see my mother’s hands making these movements. That thing of me keeping an ongoing relationship with her is part of why I took the opportunity with my dad, because I just felt like, Oh, I get it because of my mom’s death. I get it. That parent is going to stay in my life. On and on and on. They are not ending and it’s revelatory in all kinds of ways.

Your mom’s name was Katie Jo, which I love that name. And this idea, though, that you just said, I think it’s so important and I’d read a quote that you said, which, frankly, when I read this quote, I this is what made me really want to talk to you. You said, even though it doesn’t seem possible, you can always get to know another person differently than you think you can, even if they’re already dead, whether it’s through someone who knew them, finding something they wrote, etc., it’s never too late to get to know someone differently and even more deeply. We let the idea of death trap us, but we don’t have to. I literally sat down and thought about that for a long time when I when I read that and I really hope it’s true.

From my experience, it is absolutely true for me. And a couple of things like hearing that read back to me. One thing that’s missing in that is that we, because we change, we have new capacity to know the person. So, you know, one thing is like age, right? But to go through experience, right? So I am the mother of ten year olds right now. When I am the mother of teenagers, I will again understand my mother differently. And, you know, so that’s something for people who are parents. But then, you know, the experience of. Breaking through some creative obstacle and, you know, doing something really difficult and realizing that was the struggle your mother was in.

So to feel things as a human then allows you to imagine. What is your dad feel in that moment? What did your mom feel to lose her 50 year old husband that has, like, all kinds of new feeling for you when you think about who your mom was and right. And you can only do that now.

It’s so interesting because I hadn’t thought of it until I read that quote and and what you’re saying. But I think part of the reason I’m having so much trouble going through all my mom’s stuff, which is also my dad’s stuff and my brother’s stuff, is that I’m seeing them all through the eyes of the age I was, you know, I’m seeing my dad through the eyes of a ten year old kid and seeing my brother kind of through the, you know, the eyes of a 21 year old. That’s how old I was when he died and sort of seeing it just through that limited lens. It’s hard to kind of let go of things like I just found a box of my dad’s belts, like groovy belts from the seventies that I would never in a million years wear. And I remember him wearing them. But, you know, what do I do with them? My mom would always talk about how over the years, over her life, her relationship with her mother changed and her relationship with her aunt who had custody of her in her teenage years. And she came to see them in different ways as she grew. My mom would replay scenarios she had had with her mother, with her aunt, with other people in her life. And I never quite understood it while she was talking about it. But I, I get it now and I get what you’re saying about it.

You know, I would say in some sense, what you experienced was so acutely painful and bewildering, both for your dad’s death and for your brother’s death, that, like you were in states of shock. And I can imagine that feels like dangerous or impossible to like, approach or shift. And if you look at it too much or get too close to it, that that that crystalline thing might shatter.

Right? Whereas, you know, I mean, I think for me, I was devastated by my mother’s death. I was 41 years old. Right. I hadn’t had children yet. I was furious that it was happening, but it was in some kind of natural order of things. Right. And I had life experience and maturity, so. I could start to play with that set of feelings and who I was at that time and think about it. But there was so much pain in that process that by the time I got to that situation with my dad, I was like, Oh, can’t I do creative play that’s fun, that’s funny, that’s irreverent? So, I mean, I just had I just had like, this vision of, like, you could do tons of things with those belts. You know what I mean? Like, obviously you could photograph those belts, but, like, what if you, like, made some weird thing with them? You know what I mean? Like, what if you played with those belts as opposed to, you know, sort of are entombed by them? Right. Right. But I, I have so much sort of like respect and I would, again, say the word tenderness for that like ten year old child, that 21 year old young man is like, oh, you got nailed. And on a certain level, it’s like, why go near any of that again, is the feeling. But you already have that feeling. That feeling’s not going away. Right. So. So. So that maybe there’s space, which is the space I found with my dad.

You and I did something. Similarly, we both made films about our parents in anticipation of- of their death. I made a documentary with my mom for HBO called Nothing Left Unsaid, and we ended up writing a book also called The Rainbow Comes and Goes. And it was this project to just have a year long conversation talking about all this stuff I had questions about. And I’m so glad I did that and have that. And you decided to make a film about your dad’s decline. So I want to play a little bit of sound from the film Dick Johnson Is Dead, because it gets to something I always find awkward, which has been situations where somebody has died. What do you say?

What can you say when you’ve lost a best friend? Or a mother. Or your best friend and your father. All I know is that Dick Johnson is dead. And all I want to say is long live Dick Johnson.

I know you weren’t speaking in this context, but I love the idea. And I’ve been thinking about this ever since of like what if after one said, you know, I’m so sorry for your loss, which sounds so cliche and I keep coming back to it because I am so sorry for your loss, but I love that idea of saying like, long live Dick Johnson, you know.

Long live Gloria Vanderbilt. Right. I mean, I think you do need permission to say something like that to someone. Right.

Right. I wouldn’t throw it. It’s too startling for a lot of you know.

But on a certain level that change up. Yeah. That like you don’t have permission, but you’re like affirming something who, you know, that’s like, that’s really crazy territory.

You know, in Ukraine famously now, people know this when people greet each other now. One person says, Long live Ukraine. And the response to that is long live the heroes. And it’s somewhat of a controversial phrase because it was used by nationalists during the Second World War. But it is to me, such a powerful exchange that people in Ukraine, in the midst of war, have. It comes to mind when-

-Because there’s something about it that’s so affirming and and also empowering and the passing of strength and determination.

Right. This is what we’re this is what we’re fighting for. Yeah. To be alive and to be not forgotten.

Kirsten’s film Dick Johnson Is Dead, follows her dad as he moves in with her after having to retire as a psychiatrist because of his dementia. It’s a documentary, but it’s also got a series of really funny staged events, and I know this is going to sound weird, but she films her dad getting killed in a bunch of totally unexpected and kind of hilarious ways. In one scene, he’s killed by a falling air conditioner.

Clip from Dick Johnson Is Dead

00:21:16

She kills me multiple times and I come back to life. It’s Groundhog Day all over again. The resurrected dad. The ressurected dad haha.

And I got to say, I. I dreaded watching the movie. I did not want to watch it. I didn’t know anything about you, but I sort of read a synopsis, and I just didn’t get it. I thought, I don’t get this. It’s so I just don’t get this.

Were you offended by the idea?

No, I wasn’t offended. I just did not understand it.

And then I watched it and I loved it. And I loved from the first moment when you killed your father with an air conditioner, which is an odd sentence to say, but I got it. And then to see him get up, I understood then what you were doing, which I didn’t understand before. And then the um I don’t know why I’m-

The scene where you had your dad’s funeral in your family’s church and his loved ones, people who knew him his entire life came and spoke and said what they would say at his funeral, and he was able to watch it while he was still present. I just thought, what a gift to have given your dad and to have given the people in that room and yourself. One woman stood up at the funeral and said, I might have been crying when I wrote it down, so it’s always hard for me to read. She said, As long as my memory lives, the memory of him will live in me.

You know, I was like, I can’t even believe she’s saying this right now. Like, it’s just killing me. I just I mean, is this grief stuff crazy, Anderson? Like, it’s just the way it hits you. Just like the last two days. I’m just, like, all of a sudden, like. Just, like, start crying for no reason. Like, out of the like the way it hits us. Blindsides us. And that feeling. Oh, you have it all the time when someone has dementia because you, like, think, you know it’s happening and then boom. So that mechanism was like, we got to build this into the movie, right? Like, I’m going to blindside you even if you know I’m going to kill my dad, if you know I’m going to kill him with the air conditioner.

Maybe just explain, first of all, the idea behind repeatedly killing your dad.

Yeah, well, I don’t even know if I totally get it, but the impulses behind making this movie sort of came in these weird waves. Like one. I had a dream that this man in the casket sat up and he said, I’m Dick Johnson. I’m not dead yet. So, like, I felt urgency. And then I had this idea about doing the funeral that came out of the blue from that dream of that person sitting up. And then I was just like, Oh, we’re going to make a funny movie. And I didn’t even know where that came from in me. And I was like, I’m going to kill my dad over and over till he really dies for real. And I was you know.

Just to be clear, in the film, it’s not you killing your dad. It’s it’s-

Good point. Good point. I mean, I mean, the idea was that my-

-Father dies accidentally.

In a number of over-the-top ways.

In a number of over the top ways. And honestly, I mean, one of the like painful and crazy things about this is when I had this idea, I really imagine these super over-the-top deaths for him. I literally wanted to put him on an ice floe and float him out into the Arctic. I wanted to catch him on fire. So I was like thinking like these big stunts, like big movie stunts.

I heard you wanted to get Jackie Chan involved.

Oh, my God, I totally you know, I went to Hong Kong. I met this incredible stunt person who knew Jackie. I was, like, working on getting Jackie, but one like the minute we tried to work with, you know, a stunt person, we realized my dad is, like, barely capable of stepping off the sidewalk. I cannot put him on an ice floe by himself. But two finally, it dawned on me, it’s like if he dies, he can come back to life. You know, I come from Seventh Day Adventist people, so I’ve got like the deep Christian myth in me that, like, Jesus got killed and he came back to life.

That’s what I felt. I felt the joy each time he was resurrected. I mean, I there was the shock of the air conditioner falling on him on the street. And then you maintain on the shot and then you see people coming in like taking the plastic air conditioner off and picking him up. And you feel this joy and that when he listens to his own funeral and he hears all the extraordinary things people are saying and through tears, they’re speaking.

Clip from Dick Johnson Is Dead

00:25:55

See you later, Dick.

And then he comes out and he walks down the aisle and people are standing and applauding him. I mean.

What would you ask for? What more can you ask for? And so I was thinking about like how this line between life and death is like you can observe life, you can only imagine death. And then this thought like, oh, cinema, cinema can like do this like wind, rewind play thing where it’s- where we can go to the edge of death and then come back again. So there was this sort of freedom of it’s okay to imagine my father being killed by an air conditioner dropping on his head. He thinks that’s funny.

Well, it’s also okay to, in the midst of sadness and loss, you know, to laugh and to have things which bring joy and happiness and and humor. I laughed so much with my mom in the last two weeks of her life. I’ve said this before. I- by recording her laughing, I discovered for the first time that my ridiculous, girlish giggle is the exact same giggle that she had. And I never knew why I laughed this way. And it was only after hearing the clips again that I realized, Oh my God, that’s my mom’s laugh.

I love that you have the same giggle. You know, my kids and I were recently reminiscing about when we were coming up with stunts for Dick Johnson Is Dead. We would have these crazy conversations at the dinner table sometimes out in public. Me, my kids, my dad is like, how are we going to kill dad? And the kids recently brought up, remember that couple who was eavesdropping on us? It’s just like, who are you people?

That is like, I’m building something with my kids around a new way to be around death that it’s not only something that you have to be respectful, hallowed, grieving, sad. It’s also like grief can also be playfulness. Grief can be invention.

And their name can be spoken without the heaviness of that grief.

Which is hard. I mean, it sometimes takes time.

I want to play another thing you said. It’s about brief moments of joy from the film. Dick Johnson Is Dead.

Clip from Dick Johnson Is Dead

00:28:25

It would be so easy if loving only gave us the beautiful. But what loving demands is that we face the fear of losing each other. That when it gets messy, we hold each other close. And when we can, we defiantly celebrate our brief moments of joy.

That’s probably another reason you made this film, and it’s one of the reasons I did that project with my mom was to collaborate with my kids and my mom, you collaborate with your dad and spend time with them on something that was about them and honoring them and to be with them and also share them with so many other people. It’s like when I walked in the room, one of the first things I said to you is, I love your dad and I feel like I know your dad. And you know that woman who stood up and said, As long as my memory lives, the memory of him will be in me. I now have Dick Johnson in my head, hopefully for as long as I have memory.

Clip from Dick Johnson Is Dead

00:29:31

Yes, yes, yes, yes. And I- I mean, I can’t even tell you. How crazy is that? How crazy is that? That, like, I could transfer Dick Johnson to you makes me so crazy happy. But, you know, when I came in here and we were talking earlier, like I wanted you to tell me about Gordon Parks. Right. And Gordon Parks is-

Gordon Parks, by the way, is a legendary filmmaker, poet, writer, photographer, first African-American photographer for Life magazine, first Black director in Hollywood to make a major Hollywood picture. He directed Shaft. And he was a lifelong friend of my mom’s.

An epic human who I turned to over and over again to help me question understand, think about like, what am I doing with a camera? What does it mean? What does this work mean? Right. And Gordon Parks is so alive for me. We can reach across time and space. You and me. And I can give you Dick Johnson and you can give me Gordon Parks. Right. And I think that’s the thing about being alive. Is that we’re carrying like this multitude of people with us. And some of those people are like ancestors who didn’t get a chance to leave anything behind. No stuff, no creative work. They just survived. But somehow they gave us life, right? And then other people, you know, are literally like your mother’s, like the 20th century. You’re dealing with the entire 20th century in American history. Right? It’s a big deal. It’s a lot there. And then you have all the part of it that’s personal and abstract and your own and private, and you don’t want to share it with anybody. And you’re grappling with, how do I get to be just me and do what I want to do or what, you know, sort of obligation do I have to that legacy?

My legacy is an entirely different one. And I would say, like every human’s equally as rich and full and complicated, and yet there’s less evidence of it.

And, you know, I think in some ways, like, some of this stuff is so emotionally hard that we forget that our creative spirit can, like, find a new way. So I think that’s the thing that I’m advocating here is like invent new games with these people. And, you know, at a certain point, like, we got to live with the living. Right. Like you and I know, like we spent a lot of time on our parents. We spent a lot of time on the dead ones. You know, we should totally call my dad. Yeah, yeah. Okay. Yeah, we should totally call him because he’s still alive. We can call him. Mm hmm. And you know that feeling? It’s like you’re like, I got my phone, the numbers in it, but the person is never going to pick up again.

I think of him I was like, let’s call him.

God, it’s making me teary eyed. Just that thought of like-

Yeah. Yeah. Because I still see my mom’s number in my phone, and it’s- it’s so strange. It’s startling.

Yeah, let’s call him. I got to. I turned off my phone. So we got to.

Here’s the thing. I have no idea what my dad’s going to say, but I’m not afraid of that because I did bottle the essence of Dick Johnson.

Right, you know who my dad is, so even if my dad says something crazy, I’m okay with that.

Good evening. How may help you.

Hey, it’s Kirsten calling.

Oh, my gosh. Kirsten, it said CNN- we were like who knows us from CNN?

Well, I’m actually sitting here with Anderson Cooper talking to him about dad. And so-

Oh really? Oh, my goodness. Oh, um, hello Anderson Cooper, so nice to meet you. I watch CNN all the time.

Oh, that’s so nice, you’re the one. I appreciate it. I- thank you, thank you so much for what you do. You help so many people.

Oh, my goodness. My pleasure. Dr. Johnson you’re not going to believe this.

You know, I am in New York City, and I’m in the CNN building, and I’m here with a great journalist named Anderson Cooper.

You’re having a good time, aren’t you?

I am having a good time. What do you have for dinner, my friend?

Yeah, I know. Did they give you any ice cream?

No ice cream. That’s so wrong.

Right. Right. You got that right, my dear.

We were just saying with Anderson how cool it is to be able to call you.

Yeah, this is pretty good. This is a good connection.

It is. It feels like you’re right here with us, is what it feels like.

You’re in New York City, huh?

Not walking the streets. I’m sitting in a- I’m sitting in a gray room with microphones, and I’m talking to a journalist named Anderson Cooper.

Oh, yeah, I’ve heard of him.

I know. Isn’t that cool? Well, he-

You know what he said about you? He said, I love Dick Johnson.

He did! Yeah. He saw our movie, and he was like, I like that guy.

Yeah. What do you say? Do you say you love me?

I love you so much. I will love you forever and ever. And as you know, you are the best father in the world. So it’s easy to love you.

Thank you, sweetie. I love you dearly.

I love you dearly too. Okay. Bye.

Yeah, but you know what I don’t do? I cannot call every day. Guts me.

It’s really hard. Yeah, because he’ll get on for, like, a minute or two and then, like- he’ll just say over and over, I just want you to know that I love you.

And it’s just like. Like that’s literally, like, the best thing a parent could say to you. And yet, if it’s the only thing a parent is saying to you, it’s just like, okay. Like, my heart is now, like, ripped out of my chest, laying on the table at a certain point, you know? You can’t tap into that every day you know, which I think is our challenge with grief. Right. Like, you circle around it. You- you go back in, you go back out like, you know, and I could it would-

You have to kind of face it when you can face it and put it aside when you need to because you need to a lot.

I mean, if I’m somebody sitting listening to this who has a loved one who they have not sat down and recorded, I would urge them to do this immediately.

Because they’re such- you have no idea the ripple effects of hearing somebody’s voice after they’re gone or your children who aren’t even born yet, how they will feel. And anybody can do that with anybody they love.

They can. But I still would say like a camera or a recording device brings death into the room because it brings the future into the room. So if you were a child saying, I want to sit down with you, my parent, and ask you questions, the implicit thing is because you’re not going to be here someday.

And I think that’s hard. And I think that’s why in so many ways, people get intimidated.

Yeah. For anybody listening who is facing a situation with a parent and dementia or just any kind of loss. Do you have any advice?

You- I mean, it’s not advice. I’m just going to say I’m going to affirm to you, you can make something new with them.

With the person you’ve lost or are losing.

Yeah. Make something new with them. Surprise yourself. So I think, like, that thing of, like trying to keep getting the old thing from a person that you can’t get, like if you’re knocking your head against a wall. Step away, like just turn in a different direction.

Even if they’re already gone.

Even if they’re already gone. I’m asking myself this from- with my mom. Like, what new direction can I go in with my mom right now?

It’s so interesting because my mom, toward the end of her life, told me that toward the end of her life, her relationship with her aunt completely changed. Her aunt was dead. You know, long- decades. But she saw her aunt differently. She saw her aunt through much more sympathetic eyes and was from reading some old letters that I had found in storage that I showed to her. And it’s exactly what you said. It was doing something new with somebody who had been dead for more than 50 years.

Yeah, it’s really- I learned a lot.

Oh, my God. Me too. Is it helpful?

Yeah, it was helpful to me.

And that means so much to me.

I just want to reiterate one of the things that Kirsten said, she talked about not letting death trap us in terms of our relationships with someone who’s died, as she said, that parent or that person is going to stay on in your life. They are not ending and you can still get to know them more deeply. That’s how I feel about my former nanny, May McLinden. I’m getting to know her more now through the feelings I have caring for my kids. And, and that feels good. Long live May McLinden. And that’s all there is for this episode.

Next week, I talk with someone who I’ve always admired, but now that I actually know her, I love her. She’s a remarkable artist, composer, Laurie Anderson, if you don’t know who she is, you should just Google her now because she’s kind of just she’s extraordinary. Her husband is a rock legend, Lou Reed. He died ten years ago, and Laurie and I talk about grief and loss and what she believes happens when someone we love dies.

I think people turn into other things. They turn into music, sometimes they turn into- sometimes a hobby. I think I was mentioning once when I was coming into Prague that I saw oh, Vassilav Havel International Airport and Havel was a friend of ours. And I thought, how did he turn into an airport? Well, people do, they turn into other things. They turn into ideas, they turn into, uh, often into love, you know, of like, wow, I loved my grandma and so much, she was so sweet. And then that love is inside you. So that that’s it. That’s the monument of that person.

All there is with Anderson Cooper is a production of CNN Audio. The Producers are Rachel Cohn, Audrey Horowitz and Charis Satchell. Felicia Patinkin is the Supervising Producer and Megan Marcus is Executive Producer, mixing and sound design by Francisco Monroy. Our technical director is Dan Dzula, artwork designed by Nichole Pesaru and James Andrest. With support from: Charlie Moore, Jessica Ciancimino, Chip Gray Grabow, Steve Kiehl, Anissa Gray, Tameeka Ballance-Kolasny, Lindsay Abrams, Alex McCall and Lisa Namerow.